High-Res All-Embracingly Defined

I know some of the people who worked so hard on this and they may well hand me my head on a platter. But as your Audio Editor, it's my job to evaluate the effect this standard will have on my readers. It's by no means all bad but some aspects niggle at me.

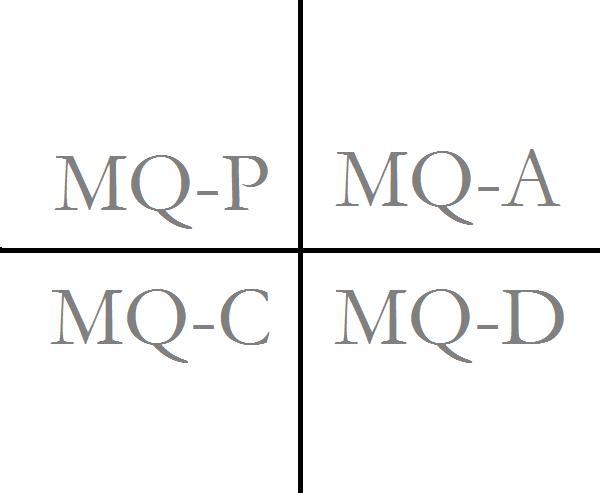

First the good news. A communiqué from the Digital Entertainment Group, the Consumer Electronics Association, and The Recording Academy has given form and substance to the hitherto foggy notion of what constitutes high-resolution audio. First, they define high-res audio as "lossless audio that is capable of reproducing the full range of sound from recordings that have been mastered from better than CD quality music sources." Using the designation MQ, they designate four different forms of Master Quality Recordings:

MQ-P: From a PCM master source 48 kHz/20 bit or higher; (typically 96/24 or 192/24 content)Have you spotted the first problem? It's one of internal consistency. High-res audio is defined as coming from "better than CD quality" sources. Yet the third designation, MQ-C, is CD quality. Come on, folks, make up your minds. Either MQ is better than CD quality or it's not. For anyone who is confused, I've already taken a stand: CD Quality Is Not High-Res Audio. Not that CD quality necessarily sounds bad—I just want the nascent high-res movement to aim higher. DEG, CEA, and TRA should have resisted the temptation to grandfather three-decade-old Red Book CD audio into its definition of high-res.

MQ-A: From an analog master source

MQ-C: From a CD master source (44.1 kHz/16 bit content)

MQ-D: From a DSD/DSF master source (typically 2.8 or 5.6 MHz content)

This inconsistency could have been avoided if the initial definition had said "CD quality or better" as opposed to "better than CD quality." But I'd say the definition is correct as it stands. It's the MQ-C designation that's problematic.

I'd also have preferred the initial definition to distinguish between uncompressed audio (just the bits, ma'am) and lossless audio (packed and unpacked to avoid losing a single bit). But the blanket use of the term lossless to cover both does no one any serious harm. In terms of sound alone, the distinction is not crucial, though in terms of file size, lossless-packing files are more efficient than uncompressed files.

Another potential source of confusion is the MQ-P designation. Again, the HRA sages want to have it both ways. MQ-P is "20 bit or higher" but "typically" 24-bit. This probably refers to ancient digital recording and analog-to-digital conversion technology that used 20-bit processing. Again, the impulse to let obsolete digital masters sneak under the velvet rope muddies the definition of HRA. Today everything is 24-bit from Abbey Road Studios to the kid sitting on the edge of his bed recording his $129 Fender Squier Bullet into a laptop. The standard should set 24-bit as the minimum.

However, if 24-bit is a given, the 48 kHz (and up) sampling rate is not too severe a limitation. I've heard some 24/48 and 24/88.2 FLACs that sound great, and 192 kHz is probably overkill. Universal Music Group's Pure Audio Blu-ray releases set a minimum of 24/96. That's probably a good target for both the industry and listeners. Yes, it may be better than our ears can discern, but that headroom is the whole point of HRA. It sets a target higher than human perception so that the listener can stop worrying about whether the source material is good enough and redirect his attention to other imperfections in the listening environment, such as equipment, acoustics, and the sad lack of Shun Mook Mpingo discs in the average home audio system (just kidding about that last one).

The remaining two categories don't pose any particular problems. MQ-A, for analog sources, is a necessity, not only because so much of recorded history is analog, but also because the best analog recordings can be truly high-res. Not all, but some. I'm guessing MQ-D, for DSD sources, has been included at the insistence of Sony, the originator of the Direct Stream Digital format, as well as the small but growing number of download retailers supporting the format. Original DSD recordings and DSD transfers of high-quality analog recordings are both worthy of the MQ designation.

Despite the abovementioned reservations, I wouldn't call the MQ standard a botch. The committee, herding an extraordinary number of very skittish cats, did what it had to do, and an already knowledgable person who knows how to read the tea leaves will find most of these distinctions useful. For instance, if you want something better than CD-quality material, having CD quality designated MQ-C would be helpful because it forthrightly labels something you'd like to transcend. MQ is like the CD format's SPARS code (DDD, ADD, AAD, etc.): a useful form of shorthand for those in the know. My greater concern is for the less knowledgable listener who needs a clear vision of what high-res audio is and is not. This less savvy listener might assume everything designated MQ is of equal merit. And that is not the case.

Is there anything the MQ standard does not acknowledge as HRA? Yes. As all-embracing as it is, MQ does exclude lossy audio—in other words, formats such as MP3 and AAC that discard most of the data to achiever skinnier file sizes. That even excludes MP3 at the maximum sampling rate of 320 kbps and superior lossy codecs such as Ogg. The committee made the right call by including only "lossless" audio formats, including lossless-packing codecs like FLAC and ALAC as well as uncompressed file formats such as WAV and AIFF.

If all of this is confusing, would you like me to set some simple ground rules? Here they are: If you're investing in high-res downloads, make them 24-bit and up, and 48 kHz and up (or DSD). If you're ripping your CDs for smartphone or streaming use, they'll sound better if you use a lossless codec such as ALAC (for Apple devices) or FLAC (outside the Apple ecosystem) versus a lossy codec such as MP3 or AAC. Don't kid yourself—even a lossless CD rip is not HRA. But there's no point in degrading it. I'm ashamed to say I didn't start ripping CDs in lossless until recently, but now I do it with everything I care about. Yes, it does make a difference.

Finally, let's admit the possibility that a bad recording, mix, or master will always sound bad, regardless of bit depth, sampling rate, and MQ designation. There are so many other things going on—miking, tape saturation, mixing, EQ, compression—that even an MQ-P, MQ-A, or MQ-D master still might not float your boat. I'd rather hear a great recording in the dreaded MP3 at 320 kbps than a lousy one in FLAC at 24/96. But if I have a choice between a great recording in MP3 or CD, I'd prefer the CD; and if it's a choice between MP3, CD, and 24/96 PCM, I'd prefer 24/96 as the only truly high-res version. Whether I'd prefer DSD to 24/96 is a topic I may revisit in the distant future.

Let's also admit that even an ideal recording, preserved in an ideal master, and presented in an ideal format will struggle to show its magic in an acoustically disastrous room, or through an inferior system, or both.

But at its best, when everything goes right, high-resolution audio is worth the effort. I recently snagged 24/96 FLAC downloads of the first three Led Zeppelin albums in Jimmy Page's much publicized recent remasterings from HDtracks. They shine. Some tracks sound just like analog-sourced vintage vinyl—in other words, perfect, for the first time in a digital medium. Others get a little extra treble definition, but judiciously applied, to bring out acoustic guitar timbre. Here's a great example of high-res audio giving contemporary listeners an experience that lives up to the glory of golden-age analog, and even exceeds it here and there. A whole new generation of listeners has a chance to hear great sound. For many of them, it's the first time. This can be a life-changing experience. The future is sounding better and better.

Audio Editor Mark Fleischmann is the author of Practical Home Theater: A Guide to Video and Audio Systems.