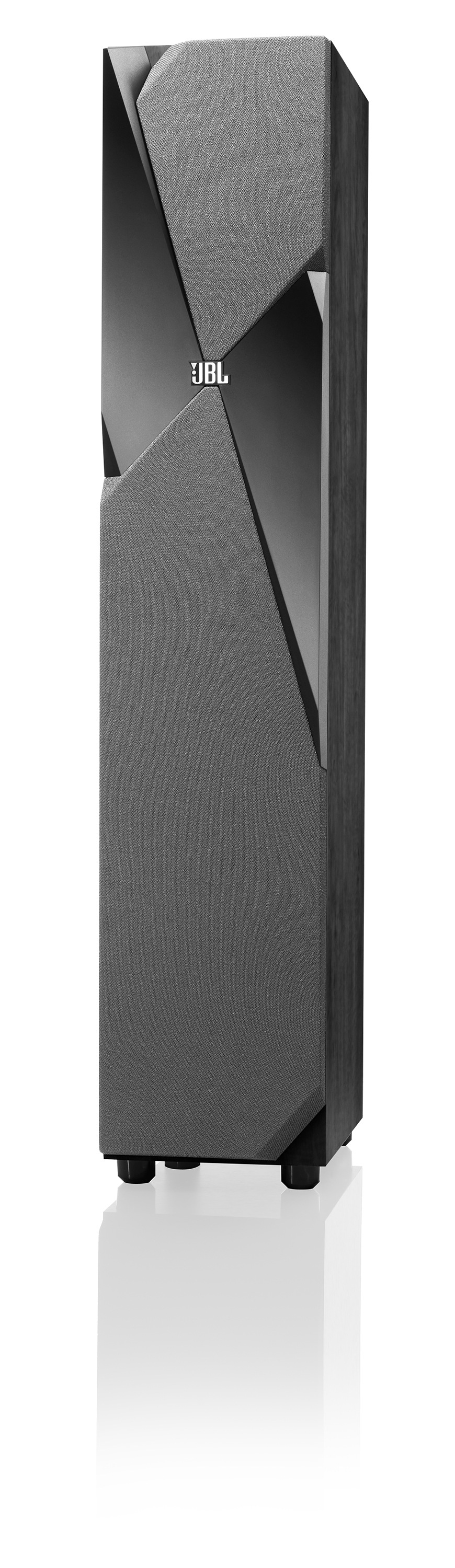

Review: JBL Studio 180 tower speaker Page 2

SETUP

From an engineering standpoint, the Studio 180 is standard stuff: a rear-ported design in a well-braced MDF enclosure with dual metal binding posts in the back. Thus, setup is typical for a floorstanding speaker. Set it out at least 12 inches or so from the wall behind it. Space the speakers far enough apart to get a wide soundstage without sacrificing a strong center image. If you like, toe the speakers in so they point straight at you — but given the Studio 180’s excellent dispersion, this isn’t absolutely necessary.

From an engineering standpoint, the Studio 180 is standard stuff: a rear-ported design in a well-braced MDF enclosure with dual metal binding posts in the back. Thus, setup is typical for a floorstanding speaker. Set it out at least 12 inches or so from the wall behind it. Space the speakers far enough apart to get a wide soundstage without sacrificing a strong center image. If you like, toe the speakers in so they point straight at you — but given the Studio 180’s excellent dispersion, this isn’t absolutely necessary.

I connected the pair of Studio 180s to my Krell S-300i integrated amp for most of my listening, and also tried them with my Denon AVR-2809CI receiver. With a gentle impedance curve and reasonable 88 dB rated sensitivity, the Studio 180 doesn’t demand much from an amplifier.

PERFORMANCE

Six years ago, I asked Floyd Toole, who at the time was VP of acoustical engineering at Harman International (parent company of JBL), what he considered the point of diminishing returns for a loudspeaker — i.e., above what price level would you cease to get large improvements in sound quality by spending more money? As one of the wisest and most important scientists in audio, he qualified his response in numerous ways, but finally answered, “Maybe $2,000 per pair.”

I think if Toole heard the $700/pair Studio 180, he might revise his answer. Tune after tune, album after album, musical genre after musical genre, I was continually amazed by how good the Studio 180 sounds. In fact, I could find only two flaws in it — one of which is inherent to its form factor, not its engineering.

Peter Gabriel’s Security has its weaknesses; it was made during the awkward early-’80s transition from analog to digital audio technology, using then-trendy gated drums as well as synthesizers that sound really cheezy now even if they were state-of-the-art at the time. Still, when I listened to my original vinyl copy through the Studio 180s, the stereo imaging was spectacular. Jerry Marotta’s drums, in particular, popped between the speakers like a Whack-A-Mole machine plugged into a 240-volt outlet. The Studio 180s wrapped my listening room with the colossal, portentous sound I’m sure Gabriel was going after but that the relatively unrefined speakers of that era seldom delivered.

Sticking with the same decade, I dropped the needle of my Pro-Ject RM-1.3 on “Come Get It” from Miles Davis’s Star People LP. I didn’t expect to hear great groove from a record player or from a full-range speaker (more on that later), but that’s exactly what I got. Marcus Miller’s slaphappy bass line thundered from the speakers in perfect, tight sync with Al Foster’s kick drum. Maintaining my stone-cold-sober, head-in-a-vise serious audiophile listening pose proved impossible; my head reflexively bobbed with the in-the-pocket rhythm.

By now I knew the Studio 180 could groove, but could it sing? Time to pull out my speaker test CD, which includes snippets of all sorts of singers. The 4-inch midrange (which in this speaker handles frequencies from 800 Hz to 3.2 kHz) got almost every one of them right, from the deep baritone of Johnny Hartman to the smooth tenor of James Taylor to the reedy tones of Donald Fagen to the soaring alto of Laura Nyro. (Only on the raspy voice of Ron Sexsmith did it choke; here, it sounded just a bit edgy and coarse.) Not only did the vocals sound natural, they sounded lush, romantic, and present in the room. Same goes for the alto, tenor, and baritone saxes in “The Holy Men” from the World Saxophone Quartet’s Metemorphosis.

- Log in or register to post comments