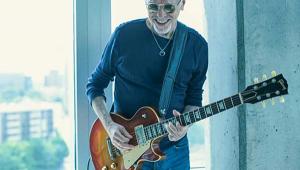

15 Minutes with Harman’s Audio Guru Sean Olive

Harman International, the multibillion company that supplies infotainment technology to automakers around the world and owns such storied audio brands as JBL, Infinity, Revel, Mark Levinson, and Lexicon, to name a few, dates back to 1953 when Sidney Harman and Bernard Kardon founded one of audio’s most iconic brands, Harman Kardon. The pioneering brand, which introduced the world’s first hi-fi (and later stereo) receiver, started with a commitment to pursue high-quality sound. That commitment endures through the work of Sean Olive, a 23-year Harman veteran. In his current role as Acoustic Research Fellow, Olive leads studies related to the perception and measurement of sound quality and is responsible for sound quality benchmarking of Harman’s consumer, professional, and automotive audio systems. He is a past president of the Audio Engineering Society (AES) and, prior to joining Harman, was a scientist at Canada’s prestigious National Research Council. We recently caught up with Olive to get his take on the state of audio today and where things are headed tomorrow.

S&V: In an article you wrote for Professional Sound magazine a couple years ago you cited the lack of “perceptually meaningful” loudspeaker and headphone specs as one of your biggest pet peeves. Have we made any progress in this area?

Sean Olive: The problem is that the current standard audio specifications for headphones and loudspeakers are almost useless in terms of indicating how good or bad they sound. Often only the frequency response is given without any level (dB) tolerance or deviations specified—20 Hz to 20 kHz, for example. The world’s worst and best sounding headphone or loudspeaker would both meet that spec, which means consumers have no means of easily differentiating a good sounding product from a bad one based on its specification. Even if a level tolerance was given, a single curve still cannot describe the quality of the direct sound and early and late reflected sounds produced by the loudspeaker. What’s worse is the science to do better has existed for some time.

At Harman we can characterize and predict the sound quality of loudspeakers with 86 percent accuracy based on a set of comprehensive anechoic measurements. Our measurements are now the basis for a new ANSI/CEA 2034-A Standard: Method of Measurement of In-Home Loudspeakers so there is hope that eventually these will be adopted as standards for the industry. We are doing similar research to develop specifications for headphones that indicate how good they sound. So some progress is being made but there is still more work to do.

A recent study reported that 55 percent of Americans typically listen to music through their laptop or PC speakers, which generally produce nothing below 300 Hz. Consumers are missing out on one-third of music’s pleasure if they aren’t listening to full-range audio systems.

S&V: The headphone market is booming and traditional home speakers are giving way to soundbars and portable wireless speakers. What’s your take on the state of today’s audio industry?Olive: We are living in interesting times. Since the 1980’s we’ve moved from large, analog, component-based audio systems dedicated to the living room to portable, digital, highly integrated, wireless speaker systems connected to the Internet. Physical media is being replaced by streamed music subscriptions, which means audio systems are always connected to the Internet. There have been growing pains from these disruptive technologies where sound quality has been sacrificed for portability, convenience, and low cost. But I see that changing. We are moving from low-res to high-res audio, or at least lossless. Premium branded audio systems have improved significantly. For many people, their cars now have more technology, loudspeakers, and better sound than what is in their homes. That has to change eventually. Audiophiles don’t want to live in their cars.

S&V: Should the audio industry (or individual companies) wage a campaign to re-ignite interest in “full-size” audio? Or is it more a question of whether anyone cares—apart from audio and home theater enthusiasts, that is.

Olive: That’s an interesting idea. In 2014, Harman produced a documentary film, The Distortion of Sound, which discussed the sound quality degradation in music recordings caused by lossy file formats like MP3. If there was a sequel it should focus on the distortion that occurs when you play high-res recordings through low-quality headphones, laptop/tablet speakers, and flat panel TV’s. A recent study reported that 55 percent of Americans typically listen to music through their laptop or PC speakers, which generally produce nothing below 300 Hz. So people are missing the bottom 3.5 octaves of music, including bass guitar, kick drum, and the fundamental pitches of the male voice. This degradation is worse than MP3. Our research has found bass quality accounts for 30 percent of the listeners’ preference. Consumers are missing out on one-third of music’s pleasure if they aren’t listening to full-range audio systems.

S&V: Do you think Hi-Res Audio will gain traction among a broader audience of music enthusiasts that goes beyond audiophiles?

Olive: In my opinion, Hi-Res Audio won’t gain a broader audience unless it offers demonstrably better sound quality and/or the recordings cost the same as the CD version. Otherwise, why will consumers pay extra for it? While high-resolution audio supports greater bandwidth and dynamic range, that doesn’t guarantee that record producers will use it responsibly and make better sounding recordings. The main problem with audio today is the lack of quality control in how recordings are mixed and monitored. There is no quality control or meaningful standards that define the performance of loudspeakers and rooms in which they are made and reproduced. A common loudspeaker standard shared by the professional and consumer audio industries would significantly improve the quality of sound