the time (we called them LPs back then, or simply just records). But CDs caught on like wildfire, threatening and then exceeding LPs dominance. Who knew then that vinyl would, one day, actually turn the tables and outsell CDs. (That statistic, however, is skewed since it refers to total sales revenue for new vinyl, not simply the numbers of discs sold. New vinyl today costs double, or more, than the corresponding CD release. But current vinyl sales are nevertheless impressive. It also helps that used vinyl itself is a significant market.)

https://core-ball.org/

Digital Follies

When the CD (now a 40-year old format!) was first introduced it arrived to a mixed reception. I was an early adopter and stationed in Germany at the time. CDs arrived in Europe shorty before they hit the USA side of the pond, so they were readily available to me on my occasional Saturday forays into Frankfurt. (I also once attended a relatively modest Hi-Fi show in that city, which much later morphed into the current and huge annual Munich event).

My first CD player was also Sony's first CD spinner, and when I first fired it up with my first CD I was...confused. The late J. Gordon Holt, then the editor of the then-intermittent Stereophile, had already gushed over the new format as he heard it on that same Sony player. I suspected that Gordon's then-current music system must have been better suited to the format than mine.

Vinyl recordings were king at the time (we called them LPs back then, or simply just records). But CDs caught on like wildfire, threatening and then exceeding LPs dominance. Who knew then that vinyl would, one day, actually turn the tables and outsell CDs. (That statistic, however, is skewed since it refers to total sales revenue for new vinyl, not simply the numbers of discs sold. New vinyl today costs double, or more, than the corresponding CD release. But current vinyl sales are nevertheless impressive. It also helps that used vinyl itself is a significant market.)

That first CD of mine sounded merely okay, though rather cold and icy. But the format gradually improved as early mastering errors were ironed out. Nevertheless, among its early and later naysayers (a small but vocal minority) digital audio has never managed to completely shake its original reputation. Many audiophiles (unlike the general public) have never entirely warmed to the digital music revolution.

Digital audio (we'll stick to PCM here, the most common form) can only exist by slicing up the source into pieces that can be manipulated as needed and either used immediately or stored for later reassembly into analog. Audio playback, or at least the loudspeakers, remains primarily analog. But isn't our hearing, at least in one respect, akin to digital? It may be analog up to the cochlea (the inner ear), which consists of thousands of tiny hairs, each responding to a specific frequency or frequency range that the brain reassembles into what we perceive as sound. I've always wondered (on the video front, though the analogy is also valid for audio) exactly what E.T. (in the movie) actually saw when he experienced a human television for the first time! It was likely very different from what we experience from the identical stimulus.

A Quick Tutorial

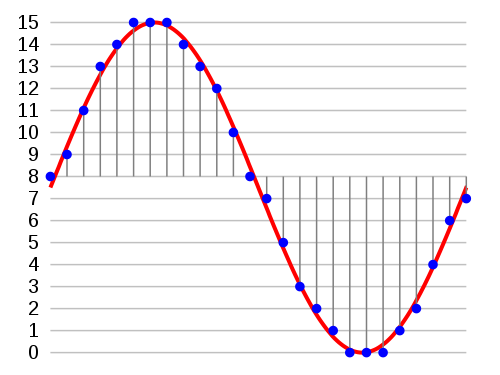

Some of the following will be very familiar to long-time audio fans, but a summary here might be useful for newbies. As noted above, digital audio carves analog sound into tiny slices, but how this is accomplished can vary. On a conventional CD the audio is split into 44,100 slices, or samples, every second. Each sample is then represented by string of 16 "bits," each of them either a zero or a one.

Why 44,100?

According to a fundamental tenet of digital audio, the Nyquist-Shannon theorem, for the maximum desired frequency to be digitally stored and then reassembled later without perceptible losses you need at least twice as many samples as the maximum frequency you plan to store. Since our hearing (for a 2-year old at least!) has a useful extension up to 20kHz, sampling at 44,100 samples per second (44.1kHz) should be sufficient to cover the range of human hearing. Why the extra 4.1kHz? I dunno; perhaps it offers a bit of extra headroom. The digital sampling is done by an analog to digital converter (ADC) and the reconstruction by a digital to analog converter (DAC).

While 44.1kHz and 16 bits are used for a large percentage of consumer digital audio, there are audio discs (and on-line, downloadable music streams) that up the ante to higher bit rates, "deeper" bit depths, or both. I'm sure this isn't news to most readers, but for those new to the party these "high-rez" releases are said to offer quality superior to plain vanilla CDs. I'll leave that to the individual to determine, but it's always been my position that the most important factor in any recording once you reach a minimum, at least, of CD quality, is the original source recording itself — the venue, the musicians, how the recording engineer handles the microphone setup, the mix, EQ, and dozens of other factors. A bad recording can't be improved much, even with a 96kHz, 24-bit release.

When DVD and, later, Blu-ray came along, the bit-storage capacity of digital discs increased dramatically. This extra space was needed for video, but the multichannel soundtracks on audio-video Blu-rays also profited and can be as high as 196 kHz at 24 bits (source, Quora discussions). Does that include every channel on the most multichannel-laden discs. I suspect so (particularly since surround and Atmos channels aren't always fully engaged), but this information isn't typically available (or trustworthy if it is), for multichannel recordings.

How Digital Compression Works

That leads us to the important subject of digital compression (to fit the sampled files into the available storage or transmission space, such as the capacity of an audio disc, audio-video disc, or a streamed music or movie file). This is an entirely different subject than dynamic compression (Google "Loudness Wars if you have all afternoon!). With digital compression it's possible to discard data in a music file prior to releasing it to the public, with the resulting degradation said to be either inaudible or unimportant to the listener. That's because some detail is always masked by other aspects of the sound and, in theory, these masked details are wasting storage space and can therefore be deleted.

Compression codecs exist to take advantage of this, deleting "inaudible" detail as it occurs, microsecond by microsecond. Bluetooth, for example, reduces the raw recorded data rate dramatically. This cut and slash technique is less likely to be used on packaged media, where the available storage space is usually more than adequate. But for streaming an uncompressed file can be unwieldy. Digital storage or transmission space, like time, is money.

Such compression, particularly if done without the listener's knowledge, can be a serious concern for audiophiles who want the best possible sound and is an important subject for home theater fans as well. And as streaming continues (unfortunately) to threaten the future of physical music and movie discs, compression could seriously impact home theater enthusiasts as well. What we hear can be no better than the source material provides.

- Log in or register to post comments

Great article, Tom! I always wonder about whether there are analogs to compression on a vinyl record that affect sound quality on that format. For example, the needle has mass, resonant frequencies, etc. that may affect its ability to track the groove on the record. Even the physical size of the needle affects what it can track - the needle cannot enter a valley on the record track that is smaller than the needle. As another example, are there limits to how frequencies that can be molded into the vinyl? Going a step further, it seems that the physical structures on the record for certain high frequency sounds would be so delicate that they would be destroyed by the needle after just a few plays of the record.

Hi,

@Old_Ben, Your right. Do a search on RIAA curve or RIAA equalization. This will address some of the things you've presented in your post.

There are a couple of errors in this article.

Compression is not always lossy - there's a lot of redundant or unnecessary information in an uncompressed PCM file (for example, if half of each 16-bit word consists of zeros, you can truncate that data and then put the zeros back when you rebuild it). A format like FLAC or WMA Lossless discards only data that is not necessary to accurately reconstruct the waveform, and will give you a final result that's bit-perfect and identical to the original PCM file.

Also, Bluetooth is not a compression algorithm, which you imply in this article. Bluetooth is a protocol for streaming all kinds of different data wirelessly between devices. There are many different kinds of audio codecs that can be used over Bluetooth, some of which, especially with older revisions of the Bluetooth spec, are lossy, and some of which can use Bluetooth 5.0's higher bitrate to stream lossless audio. AptX Lossless, for example, will deliver bit-perfect audio over Bluetooth. The only catch is that both the transmitter and receiver need to support AptX Lossless - if your phone supports it but your receiver doesn't, for example, your phone will drop down to an older codec like LDAC.

Excellent corrections, SuicideSquid

CD-quality audio perfectly reproduces the analog waveform. There is no loss, and the waveform is not "sliced up." The Nyquist-Shannon Theorem proves this. If you want an excellent video detailing how it works, search for "Technology Connections Nyquist" on YouTube.

This is of course a separate issue from DRC or lossy compression. Digital audio *can* be bad. But it isn't bad due to any intrinsic fault in the technology, rather due to poor choices in encoding.

The Whittaker-Nyquist-Shannon theorum requires a perfect sinc function be performed on every single sample then summed into a continuous function with all the other samples. A finite input into a perfect sinc filter will generate an infinite output both before and after the sample, which is literally not possible. Since the theorum requires something impossible in the real world, your whole argument falls apart.

Infinity is fine in math (which is what the Whittaker-Nyquist-Shannon theorum is, a math proof), and common in calculus (think functions whose limit approaches infinity). In reality, infinity is... incredibly rare or non-exisitent. With a perfect sinc filter, you press play and nothing comes out of your speakers. Ever. Even after the heat death of the universe you'll still be waiting because... infinity.

FYI, I'm a recording engineer and a biochemist. Weird combo, I know. I can tell you that what comes out of the mixer and what comes out of the recorder (digital or analog) always sound different. Unless you mix "in the box" but that has its own sound too (and no recording sounds like what comes out of the mic pre-amp). The A/D/A process changes the sound, but is far less susceptable to entropy than analog (which also changes the sound). Yes, I just put the 2nd Law into a conversation about audio and stayed on topic (twice!) :D

N.B. to Mr. Norton - no, I didn't read the article though I assume it's well written. Came to the comments because I knew someone would say "nuh uh" after seeing the graphic and headline.

Mark Phillips.

In the video mentioned above, the waveform is reproduced perfectly when an analog signal going into the ADC and coming out of the DAC goes through a low pass filter and is thus band limited. I suggest watching it. He demonstrates it pretty convincingly.

In a signals and systems class you might do some of the actual math to digitize and reconstruct an analog signal. The math can go back and forth from analog to digital and back again perfectly every time.

The really, really hard part is implementing a real world DAC that can do that. One of the problems, time from minus infinity to plus infinity, is mentioned above. All of those tradeoffs produce artifacts or leave things out. What we like or don't about certain DACs has to do with the designer's tradoff decisions.

It's similar to the challenges of making the transition from an electrical signal to a physical geometric surface back to an electrical signal that a cutting lathe and a phono cartridge have to negotiate. Or from an electrical waveform to an acoustic waveform that our speakers produce.

DACs have improved quite a lot since the early days of CDs.

But back in the day, quadrophonic LPs demonstrated that the media had a lot more bandwidth for detail than two channels of 20-20kHz. We're also a lot better at pulling out those details in two channel LPs today than 40 years ago.

My CDs have never sounded better, and my LPs have never sounded better.

Cool stuff.

Fascinating insights into the evolution of digital audio and the impact of compression. As a longtime audiophile, the nuanced history of CDs resonates. The balance between sampling rates and human hearing is crucial. The discussion on compression and its implications for streaming heightens awareness. Source quality remains paramount. Looking forward to more in-depth exploration. https://paybyplatema.site/

I am extremely impressed with the exceptional quality and craftsmanship of the geometry dash 23 product. It is evident that great attention to detail and durability were prioritized during its construction. This product is built to withstand the test of time.

The evolution of digital audio and the influence of compression are captivating. As an avid audiophile, the intricate CD history strikes a chord. Balancing sampling rates with human hearing matters. Discussing compression's streaming impact raises awareness. Source quality stays vital. Eager for deeper dives ahead. https://myolsd.top/

Vinyl is still the best! I personally think that Digital can never outcompete it. Our new office soundsystem at Gutter Cleaning Stoke-on-trent is all vinyl-based, and the sound is so crisp. You simply can’t beat analog on quality.