The S+V Interview: Mikael Åkerfeldt of Opeth

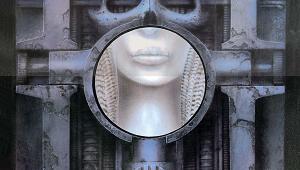

S+V: Heritage (Roadrunner) has a very natural, open sound, with a lot of the kind of spacious environments we associate with Pink Floyd albums or even jazz records. Steven Wilson was on board to mix this one, and you’re finally credited as “producer.”

ÅKERFELDT: Generally, I would say that I’ve produced every Opeth album; I’ve just never taken the credit for it! In reality, I always have been producing the records, but I’ve been unaware what “producer” means; I thought the producer was the engineer. We’ve never had anyone interfere with the music, the songwriting, or anything else. We’ve always just had engineers, and sometimes those were engineer/producers, like Dan Swanö on the first few albums. He’s also a songwriter and had a few suggestions. And we had Steven Wilson too, but he mostly worked with my vocals, some lead guitars, and the keyboards. But no one has ever produced for us in the sense of getting into the songwriting. It’s been more about suggesting a harmony over a vocal part, for instance; more of a co-production thing.

S+V: Heritage has a great sense of space and ambience, and that all really speaks to the listener. It’s an exciting development for Opeth, as it suggests a lot of new possibilities.

ÅKERFELDT: It’s been really exciting for me, too. I have so many references from the records I’ve been listening to myself, especially those old prog records. And, of course, Steven knows a lot about that kind of stuff, too. I knew what I wanted this record to sound like; it was just a matter of getting there. The whole recording was just good old microphones, a nice old studio, a nice old Neve desk, a good room, and everyone happy to be there and wanting to play the best they could. We had the songs. It was just a matter of pressing the RECORD button.

Steven did mix Heritage, but, of course, I was very involved with that, too. For instance, he tried to do a few things, like re-amp some of the guitars. I’d say, “Wait, something sounds strange here.” “What do you mean?” “The guitars sound too clean. Did you do something to the guitars?” “Uh, maybe. . .” In the end, I got my views through, and he did an amazing job. It was an easy mix, ultimately, because it was about adding effects, getting the levels right, panning, and all that. Say we had two Mellotrons coming in, and then there’s a lead. I’d say to him, “Maybe we should have that lead a little more to the right.” And Steven would be pointing, “Here?” “Maybe another decimeter to the right!” It only took about 4 days. It was very quick; it was just a matter of audio details. It was never about a drum recording sounding like crap, or a performance that was awful and needed to be fixed. It was just about getting the levels right.

S+V: There was plenty of hullabaloo in the metal scene about the lack of death-metal “Cookie Monster vocals” on Heritage.

ÅKERFELDT: Many metal fans — myself included, when I was younger — have a kind of tunnel vision. It’s supposed to be done a certain way. There’s a pretense of open-mindedness: “Yeah, they’re a progressive band, they’re supposed to progress.” But often it’s only something people say. When a band actually does change, it’s like, “What the f— was that?” I can totally understand that, but I would never adapt to that myself as an artist. This is why I made the decision to become a musician all those years ago, why I quit my job and went into poverty: because I love music so much that I wanted to go for it.

I hate people controlling me. Maybe it has to do with my personality. I hate not being in complete control of my own life. When I pursued this musical career, it was to have the freedom to live my dream, and I will never let anyone to restrict that dream. We’ve been around for a long time now, and we always change. If people expect us to stay the same, I don’t know what to say except, “I’m sorry, that’s just not going to happen.” We have a career, of course, and people might say, “Aren’t you afraid of losing fans?” and the answer is, I’m not. I’m more afraid of losing myself.

S+V: The opening song, “Heritage,” which only features piano and upright bass, announces that this is a very grown-up Opeth record.

ÅKERFELDT: I think it sets the tone for the album in a nice way. It’s an unorthodox song for an Opeth record. It’s completely inspired by a Jan Johannsen record from 1964 called Jazz På Svenska, which means “Jazz in Swedish.” It’s basically Swedish folk music interpreted in a jazz way. It’s just piano and upright bass, so it’s very clear where I drew my inspiration for writing “Heritage.” It’s very Swedish-sounding, and that’s what we wanted to get. With the album title, Heritage, the idea is that we’re taking care of our Swedish musical heritage with that sort of piece being on this album.

S+V: What would you say defines music that sounds “Swedish”?

ÅKERFELDT: It’s some kind of melancholy that comes from the folk music that’s hundreds of years old. I’ve never been a complete folk-music buff exactly, but it’s something that has always stuck with me, something that feels like home. I mean, I can put on that Jan Johansson album when I’m in India, and it’s like, “Wow, I’m home.” It’s in our DNA, and even bands as different from us as ABBA, who were heavily influenced by Swedish folk music, have that feeling and sound. To this day, Benny Andersson, the main songwriter in ABBA, is playing folk music with the Benny Anderssons Orkester.

S+V: Heritage certainly signifies a big break with heavy metal and death metal.

ÅKERFELDT: Heavy metal is my real roots. It’s what I grew up listening to, and what I still listen to quite a lot of the time. But mainly for me, it’s ’70s and ’80s metal music. Heavy metal music has grown to be quite massive over the past few decades. But for me, it’s been watered down. It’s hard to tell a lot of the bands apart. To be honest, I’ve lost a bit of interest in it for that reason. Even if that’s where we made our career, I really feel like we don’t belong in that scene anymore.

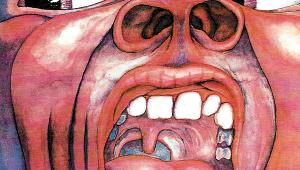

S+V: The guitar tones aren’t “metal” anymore. “The Devil’s Orchard” sounds quite a lot like King Crimson, and “Slither” recalls vintage Ritchie Blackmore.

ÅKERFELDT: What we did was very deliberate on “Slither,” which is a tribute to Ronnie James Dio. We played Stratocasters, like Blackmore. Most of the rhythm tones on the album are Stratocasters with single-coil pickups, and it’s more of a trebly, slightly thinner sound. We wanted the bass guitar to take care of the bottom end on this record. I think that for the first time, we’ve actually gotten a production where you can really hear everyone. On most contemporary metal records, the bass guitar may as well just be the bass knob on your stereo; the bass guitar just plays unison riffs with the rest of the music. So we wanted to approach it differently, and I think it gives us a new edge, something that we’ve never had before.

S+V: There’s less distortion and gain on the guitars. Did that mean you had to work a little harder?

ÅKERFELDT: You have to. When you have less distortion, you have to play better. When you have a big, high-gain amplifier, active pickups, and tons of distortion, you don’t really have to be able to play. To be honest, that’s one of the things I think is pretty sad about the metal scene today, because back in the day, metal musicians were known to be fairly good players. And today, in a way, it’s all come down to technology. Not only can anyone sound okay on the right equipment, but the engineers in the studio make sure everything sounds okay. They splice everything up, quantize and fix it, and in the end it sounds more like a computer playing than a group of humans. And that’s something we wanted to get away from — completely away from where the contemporary metal scene is heading.

S+V: There are certainly fewer great metal soloists than there used to be.

ÅKERFELDT: There are a lot of technically good players, but there’s very little real personality. [Opeth bandmate] Fredrik [Åkesson] is an amazing lead guitar player, and I wanted him to play as diverse as possible, not just go for the fastest run. We wanted to mix the traditions of Blackmore, David Gilmour, and Andy Latimer of Camel — the type of guys where you hear a few seconds of their playing and you say, “Hey, that’s David Gilmour.” We wanted to have these different personalities come through. Fredrik can play anything, so it was amazing for me to be able to come up with a song like “Slither” and ask him, “Could you play something a bit Blackmore-ish?” And he’s like, “Yep, sure.” There’s some footage of him soloing on the DVD that comes with the Heritage Collector’s Edition, and he gets so emotional. You can see him making all the guitar faces, the white eyes and everything. It’s crazy.

S+V: Your own lead style leans more toward legato playing, a bit like Allan Holdsworth, or moodier bluesy stuff, not unlike Gilmour. I really like the outro solo to “Häxprocess,” which I assume you play.

ÅKERFELDT: Yeah, I’m doing more of the slower leads, because that’s what I do best: long, slow notes. Generally, Fredrik is the lead guitarist, but if there’s a place where I think my style is most appropriate, I’ll take a lead. I never was a true shredder-type guitar player, though I did have the wish to be one when I was younger. That was my dream, but I guess I changed. Now I have Fredrik, so there’s no need for me to do that. Also, I want him to feel that he’s the lead guitar player, and I’m the songwriter.

S+V: “Nepenthe” reminded me of “Red Alert” by the Tony Williams Lifetime with Allan Holdsworth. [“Red Alert” can be found on the 1992 compilation, The Collection —Ed.] Were those sorts of fusion sounds in the air when you were writing this stuff?

ÅKERFELDT: I like Return to Forever and Mahavishnu Orchestra, the [John] McLaughlin solo records, and of course I really like the late-’60s Miles Davis records. One of my favorites is [1969’s] In A Silent Way; I love that one.

“Nepenthe” started as something meditative — a chord progression that sounded a bit jazzy, and I came up with this keyboard lick on the verse. For a while, I thought I might sing on it, and then I thought, “Nah, let’s do something f—ing crazy.” So I had Fredrik come by and I asked him, “You like Allan Holdsworth, don’t you?” and he said, “Yeah!” So we have two solos there. One is a bit more laid back, and the other one is crazy fusion shredding.

S+V: There’s an area in about the middle third or so of the record that’s the longest period of stillness and mellowness we’ve ever heard on an Opeth record, even on [2003’s] Damnation.

ÅKERFELDT: I did a lot of the work of sequencing the songs with Steven Wilson, and of course we started out with the “Heritage” piece. It’s pretty heavy at the beginning for the first few songs after that through “Slither.” Then we wanted to introduce the more experimental section of the record, with “Häxprocess,” “Famine,” and “The Lines in my Hand.” “Famine” was the last song I wrote, and at that point I felt that we had a whole lot of regular songs, which allowed me to be extra f—ed-up with “Famine.” It’s very enjoyable for me to listen to, and it concludes the sort of experimental trilogy of the album. We pick it up a bit again near the end with the next-to-last track “Folklore,” then finish off with “Marrow of the Earth,” this instrumental piece that closes the record in a nice way.

S+V: I really like “Marrow,” which has an early-’70s French-film soundtrack vibe.

ÅKERFELDT: It was intended to be a vocal piece. I wrote that for Nathalie [Lorichs], who sang “Coil” with me on the last album, [2008’s] Watershed. I intended for her to sing that guitar line, but when I played it for her, she said it sounded a bit too complicated. So I scrapped it for a while, and when I picked it up again, I thought, “Wow, that’s a pretty beautiful melody. I should finish it.” I played all the guitars on that one, the nylon-string guitar and the guitar leads — again, because that’s what I can do, play melodies with as much emotion as I can. That’s my style, my influence from Camel’s Andy Latimer and Focus’s Jan Akkerman.

I love solos, but if they’re not done right, they can be a burden on a song, rather than lifting it to the next level. We only play solos if we think they can add something to the song. When it’s called for, we’re going to have it. I work a lot with every musician in Opeth in order to get the best from them and make them express themselves in the best possible way. And that goes for when I work on my solos — I want them to mean something, if you know what I mean; not just be pointless shredding. My demos for this record, for instance, were very complete and very articulate, but I just did what I thought sounded good, then left it open to the guys to interpret in the way they wanted. And the only thing I wanted from them was to make it better. That was it. We had some arguments in the studio about what was best for the song, but in the end, they were always productive arguments. It wasn’t like I was controlling. I was producing, but I’m never going to try to control each musician’s individual view of a song. Once they play their parts, that’s how they make the album their album. And it feels like I can’t interfere too much. I let them do whatever they want, as long as I feel it’s rocking.

Many people are calling this album The Mikael Åkerfeldt Solo Album, but it’s never been like that, and not for this album either. We are a band, and I’m very open-minded to what everyone thinks. Luckily, with the music I’ve been writing for the last couple of years, it’s something that the rest of the guys are able to feel as well, and something that they want to do, too. And they’re able to adapt to it.

- Log in or register to post comments