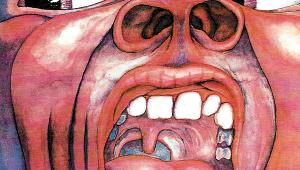

Surround Review: King Crimson

“Superb. The music is brought to life.”

That’s Robert Fripp’s own assessment of Steven Wilson’s 6-channel mix of Discipline. I have to agree.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

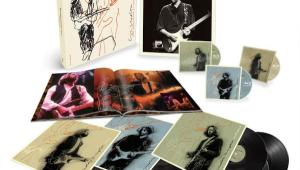

First, the facts. These two volumes are the most recent installments in the 40th Anniversary Series of King Crimson reissues on CD+DVD-Audio, with each title sporting a surround mix by Wilson. (To be precise: Wilson and Fripp are officially co-credited as mixers and producers of the multichannel versions, but Wilson was the lead mixologist.) Starless and Bible Black, originally released in 1974, was the penultimate studio album from the first wave of Crimson lineups. By contrast, 1981’s Discipline marked the revival of the band name after a 7-year break, with guitarist and guiding light Fripp retooling the concept to present a somewhat less severe but no less intricate musical approach for what turned out to be a highly receptive audience of ’80s New Wavers and old-guard progressive rockers.

Starless followed what had become a somewhat familiar template for King Crimson albums by that time: a hugely powerful opening number (“The Great Deceiver”), a bruising, riffy rocker (“Lament”), and one or two lengthy tracks displaying elements of serenity, dissonance, authority, and resolution. At the same time, this album found the band moving down an increasingly experimental and extreme path. The entire second side of the original LP was composed of two instrumentals, the title track and “Fracture,” running for 9 and 11 minutes, respectively. They are among the most challenging and rewarding items in the band’s catalog but are largely for the fearless of ear and heart.

As Wilson has done throughout the Crimson surround project, he has noticeably improved upon the somewhat sludgy sonics of the vinyl era. The 6-channel mix of Starless exhibits an overall brighter sound with perceptively more presence; that said, the original stereo mix is never altered beyond recognition. This dynamic sorcery extends to the lowest notes. John Wetton’s bass punctuations have a startling, tactile quality, as if the strings were being plucked right there in your listening room.

Following the furious introductory passage of “The Great Deceiver” — a maelstrom of sound, with Fripp’s lead guitar in the right rear speaker, David Cross’s violin in the left rear, and the rhythm section of Wetton and drummer Bill Bruford emphasized in the front — there’s a tempo change at 0:42, with bass notes from Wetton initiating the transition. It’s a good test of your subwoofer’s ability to handle the deep end without rattling or turning to mush. Suddenly, Fripp hits a discordant chord, which Wilson has placed in both rear speakers. Next pops out Wetton’s lead voice, stretched across the three front channels but isolated and magnified in the center. On the chorus, a choir of harmonized voices erupts from all corners. All told, Wilson has mixed “The Great Deceiver” to enhance the air of adventure and unpredictability that must have been Fripp’s intention in the first place.

There are other such surprises and delights to be unearthed from Starless. The percussion on the second section of “Lament” is distributed among the various speakers, with a series of paradiddles on woodblocks tickling your ears from the right rear; then Fripp’s sluicing chords and Bruford’s volcanic drum eruptions engulf you in a mad vortex of sound. The bass notes and cat-like guitar howls on “We’ll Let You Know” reverberate from front to rear and subtly circle the periphery. The sonic sculpture of “The Night Watch,” which conjoins live and studio sections, achieves a three-dimensional fullness in surround sound, especially during the stunning opening passage — again, with guitar and violin in the rear as the rhythm section thunders from the front.

The original multitrack tapes of “Trio” and “The Mincer” are missing, so those pieces had to be upmixed to 5.1 (using the original stereo masters) by Fripp and Simon Heyworth. But the wild ride resumes with the title track, a wondrous cacophony that apportions as much of its sonic mayhem to the rear speakers as to the front, making for yet another deliciously enveloping experience. And the closing “Fracture” is a monster, another study in extremes, with its constituent elements separated here and overlapping there for maximum impact. At 7:40, the performance and volume intensify, and the music suddenly feels as if it’s emanating not from all the speakers but from inside your head.

- Log in or register to post comments