Listen Up and Play Right

After 42 years in the business, ListenUp's Steven Weiner is still learning how to put together the perfect home theater—and the more he learns, the more he sees how much more there is to know. But don't hold that against him. So far, he's spent nearly half a million dollars building the ultimate demo room as part of his mission to find out.

Actually, as any professional involved in designing, installing, or reviewing these setups will tell you, there is no such thing as the one perfect home theater. The reasons for this are many, beginning with the oft-repeated fact that no two people are the same. Even if the basic room layouts are identical, a designer has to take into account individual tastes, as well as the homeowner's personal and familial requirements. And then there's the budget to consider. Unless you're one of a select few individuals with a bank account larger than the GDP of Tajikistan, at some point you're going to have to decide what you want and what you can do without in your home theater. Factor all these variables together, and you'll come up with a darn huge number of possible perfect theaters. (Scaling systems down from a no-holds-barred starting point to one that best fits a customer's particular situation— accommodating for wants, needs, and budget—is what ListenUp co-founder Walt Stinson refers to as finding the "elegant compromise.")

Weiner is undeterred by the task. ListenUp's new home theater demonstration room—two years in the making and constantly evolving—gives the Denver, Colorado–based company's salespeople, designers, and installers increasing insight into what it takes to make each individual home theater the best that it can be. "Although ListenUp has designed and installed a lot of systems over our 35 years in the business, and we have done a wide variety of projects in our stores, we just keep learning. And this system, which is a laboratory with testing-lab qualities, has been the best teacher of all."

Calling this demo room a laboratory conjures up visions of guys in white lab coats taking notes while movie buffs scamper about within a maze of plush theater chairs racing to find the box of cheese popcorn that's been placed at the best listening position in the room. As cool as that would be to see, ListenUp's room is nothing of the sort. In fact, at first glance, it's hard to distinguish from a lot of other high-end home theater rooms, with a stadium-seating arrangement, fabric-covered walls, and a theater-style curtain that dramatically parts to reveal a Stewart perforated Firehawk four-way masking projection screen.

Looks, by the way, can not only be deceiving; they're one of the first obstacles on the path to creating the perfect home theater. If you're a fan of art-deco or Star Trek–inspired theater room designs, then the comfortably unadorned surroundings of ListenUp's room will preclude you from checking off the 10-out-of-10 box on your Perfect HT Room scorecard. On the other hand, the refined simplicity of the room (created for the most part by fabric-covered panels along the walls and ceiling that conceal the speakers and acoustic treatments, plus a totally enclosed projector and soft blue neon accent lighting above the seating area) might be just what you were looking for.

Close Your Eyes and Hear. . . Nothing

However, you can't argue about the measurements of a room's acoustics. One room is either quieter than another or not, and room modes and echoes either exist (to varying degrees) or they don't. Unfortunately, although a home theater room's acoustics are the foundation upon which the system's audio performance is built, it's often one of the last issues that system designers or do-it-yourselfers address—if they do at all.

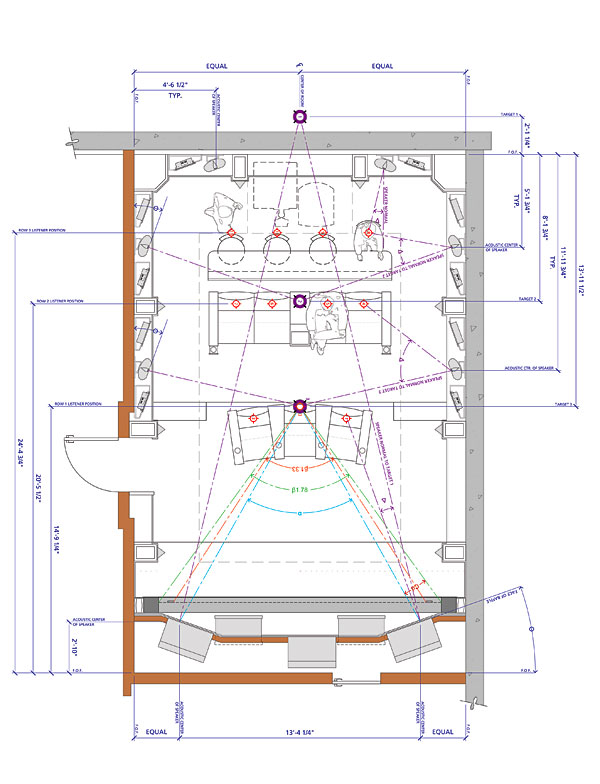

Weiner knew from the beginning that this would be an all-important consideration. Over the years, ListenUp has and continues to use a variety of room-treatment products and approaches, including the services of the folks at Rives Audio, based on the scope of the project at hand. For this room, though, Weiner turned to Keith Yates Design Group, Inc. When it comes to home theaters, Yates, the mastermind behind KYDG, is one of the most knowledgeable, detail-oriented, and reliably accurate guy you'll never be able to afford to design your room and system. Nonetheless, some famous and some not-so-famous people with more money than most of us do hire him on a regular basis. Weiner says Yates doesn't normally consider retail demo rooms, but their longtime acquaintance brought the two together for this one.

When he designs a room for sound, Yates' approach is not to mask the effects of the room's acoustics; instead, he intends to totally eliminate them. That way, what you'll hear when you play back a movie or CD is truly what's on the disc and not some approximation that's been modified by the room you're sitting in.

Although there were still some things to work through, such as moving the shock-mounted HVAC units on the roof another 15 to 30 feet further away, ListenUp's room comes about as close to sonic perfection as you can imagine. (Well, maybe. As Weiner told me, "You can always keep tweaking.") I've been in plenty of other treated rooms, and many of them leave you feeling oddly disoriented. In some, it's even difficult to hold an extended conversation. This room, by comparison, is so comfortable to be in that you might not notice how amazing the acoustics really are. Not only does it sound totally natural, but if you were led into the room blindfolded, it would be nearly impossible to get a sense of the room's large size. That's pretty much the ultimate in transparency.

Weiner likes to point out that "no one can hear a Keith Yates–designed theater other than here. All the other systems are in people's homes." Considering that you're unlikely to be invited over for dinner and a movie at one of Yates' very upscale clients' homes, that alone might be reason enough to visit this demo room.

There Be Gear Here

Interestingly enough, as much as most of us salivate over particular pieces of equipment, the A/V gear in this room is really secondary. Of course, the gear matters. You wouldn't have the same caliber picture using a sub-$1,000 480p projector rather than the new Runco VX44D with its motorized anamorphic lens. (That's almost $100,000 of the total room cost itself, by the way.) The Classé SSP-600 processor and Genelec active in-wall speakers (AIW26), active monitors (1038B), and powered subwoofer (HT6) are just as important on the audio side. (This ain't no HTIB!) In short, the whole presentation makes this room what it is.

The lighting, seating, and control system are also important to the entire experience. ListenUp used ImageCrafters to provide the lights and the lighting design, as well as a Lutron six-zone GRAPHIK Eye system. When you're putting together your home theater, one of the compromises you might make is to use a light switch and your finger as the lighting control; but it's incredibly cool to be able to dim or turn the lights on and off on command. Moreover, you can select to have them automated in zones that can light the room in different ways depending on how you're using it (movies, music, and so on). Weiner went a step further for a lighting system designed with lights behind the fabric panels that can illuminate to highlight the hidden speakers, just like the old IMAX demonstrations.

Controllier Than Thou

Behind the 8.4-inch touchpanel controller the ListenUp staff uses to operate the system is a full-blown Crestron control system. This arrangement interfaces with the Lutron to handle the lighting. It also automates things like opening and closing the red theater curtains, switching sources, and operating the Kaleidescape system. But, as you might expect, there's more to it than that. For instance, to eliminate noise in the room from the Runco projector's cooling fans, the projector is mounted in specially designed housing. Due to the restricted airflow, there are times when the housing's internal temperature gets a bit balmy. The system includes a Crestron thermostat monitor with a remote temperature sensor near the projector. If the temperature exceeds a set point, the Crestron turns on a fan to vent the excess heat. This temporarily increases the noise floor in the room, but it greatly decreases the chances of projector failure.

The Crestron system also controls the new CINEAK theater chairs that ListenUp installed just before I arrived. Aside from their high level of comfort, you can preset these motorized chairs to suit a variety of individual reclining tastes. About the only thing they won't do is keep track of the spare change, pencils, and crumbs that always accumulate under any seat cushion.

Your Room Is Ready, Sire

As much as the folks at ListenUp view their unique home theater demo room as a learning laboratory, the room also functions as a place to discover what their customers want. "It's the rare person who is totally interested in all aspects of the room," Weiner says. One customer, for example, wanted the visual impact of the room—the room's appearance, mind you—but cared little for the actual audio/video performance. "Some people glom onto the control system, some on the video, the audio, the furniture. Our objective is that each person gets the perfect thing for him or her."

Although he'd love for lots of people to come in and write him a check for the whole shebang, that's not what drives Weiner to keep on tweaking. It's the desire to create an ultimate frame of reference for consumers and industry people alike. For customers, the ListenUp staff tries to come as close as possible to the perfect concept considering each client's budget and interests. For those jaded industry pros who already have an elevated reference point, the demo becomes a slightly different story. "This is the most fun part of my job. It's fun to see someone recalibrate their experience. People come out talking about 'the room' as its own entity."

Ultimately, it's all about the experience—an experience so moving it once led a customer, a brawny contractor who'd previously shown little interest in home theater, to wrap Weiner in a big bear hug after a demonstration. In 35 years, Weiner's never been hugged by a customer before, nor had the builder ever hugged a business acquaintance before. And if that doesn't fit the definition of the perfect home theater, I don't know what does.

Q&A with Keith Yates

Q&A with Keith Yates

Q: You design theaters for film directors and Silicon Valley technologists. Why do one for an A/V installer?

A: I took the meeting because I'd known ListenUp's founders, Walt Stinson and Steve Weiner, for 25 years. I knew their history of putting dedicated, treated sound rooms in their high-end audio stores, starting with one of the first live-end/dead-end retail showrooms in the world, back in the '70s. It was clear that they get it. Real solutions don't come from sloganeering or gluing Brand-X panels on the walls; they come from top-to-bottom brand-agnostic engineering, documenting, testing, and adjusting.

Q: Why do you think ListenUp picked you?

A: I think my eyes lit up when Steve declared they needed the room to support oh-my-gawd movie experiences, exquisite two-channel stereo demonstrations, and be a sonically comfortable space to meet with architects and builders. He knew how hard it was to get even one of those things right, really right, let alone all of them, and I think my body language telegraphed my "buy-in." Second, I think my approach was different.

I wasn't trying to sell them a pat treatment program or use it as a springboard into other showroom-type projects, for example. What turns me on are technical and sensory challenges. And in retrospect, I think they'd heard that my A&E [architecture and engineering] team includes industrial-strength engineers in noise and vibration, technical power system design, HVAC engineering, acoustic testing, and so on—guys with advanced degrees who'd directed those activities for IMAX and other top-tier companies for decades before joining KYDG. At some level, I think Walt and Steve simply wanted to expose their staff and clients to our process—how we dissect problems, model some possible solutions, draw it up, and verify we got the result we wanted.

Q: Why do acoustics matter?

A: Put a blindfold on a friend, walk him or her around the house, and ask what room you're in. Their ears will pick up both the direct sound of your voice and the reflections ricocheting off walls, floor, ceiling, and other surfaces. That sequence of reflections—something acousticians call an echogram or energy-time curve—is what the brain uses to build an image that says "garage" or "bedroom" or "kitchen." Blind people are often masters at this, but we all process sound this way. Change the reflection history, and you change the perception of the environment you're in. Most home theaters are roughly the size of a living room, and, unfortunately for the movie experience, they sound like one.

Q: So your job is . . .

A: To strip from the audience the perceptual cues that give away what kind of physical environment they're in. Basically, I want to make the room stop sounding like a living room or conventional home theater or any other aurally recognizable space. My goal is not to kill room sound—a primitive and bafflingly common approach that benefits no one but the fiberglass industry—but rather to reshape the energy-time curve by pruning the spikes, digging out some gaps while filling in others, and generally recontouring it to be denser, smoother, and lacking features throughout the audience area. If you get that designed and implemented right, your blindfolded friend says, "Hmmm, sound is crystal clear here, with a subtle glow, but I'm not getting a picture of what kind of room I'm in. Can't tell whether it's big or small, rectangular or irregular, high-ceilinged or low. I'm stumped, but I love it in here."

Q: So you're not a fan of fiberglass sound panels?

A: There are only three things you can do to sound in a room: absorb it, bounce it, or scatter it. As in all of our projects, a mix of absorbers, reflectors, and diffusors covers all four walls and the ceiling. But for all the coverage, we use surprisingly little absorption. So, no, in 20 years of doing this, I don't think I've ever gotten a Christmas card from the fiberglass industry.

Q: And the payoff for movie lovers?

A: First, the room is pleasant to sit and talk in. Second, in sensory terms, movie experiences are deeper. If the soundtrack puts you in a fighter cockpit, you're there because the brain isn't presented with a conflicting set of cues disclosing that you're actually in a living room watching a movie about someone in a cockpit. Get the acoustics right, and the brain tends to accept that you're wherever the filmmaker takes you—the Amazon rain forest, a Jeep in the Sahara, an opera house, an alien invasion. Sounds technical, and it is, but sit down at ListenUp, and I suspect you'll say it's magic.

Keith Yates Design Group, Inc.

www.keithyates.com

HT on a Massive Scale

HT on a Massive Scale

by Gordon Shackleford

In the consumer electronics industry, it's difficult to not get caught up in the self-adulatory rhetoric and puffery that permeate our business. That said, it becomes a difficult task to aptly describe the unique achievement of the ListenUp theater. It's the most complete, well-conceived, and implemented theater room I've ever seen—and I've visited many large-scale private theaters during my 10 years as director of sales for Faroudja laboratories. It seems that the ListenUp theater has addressed every element of audio and video with the most compelling and interesting technologies available today.

In this room, science trumps hype and demonstrates a thoughtful and elegant selection of truly synergistic components. After science has been properly addressed, performance must be measured by the only standard that truly matters: the profundity of the cinematic experience that the room provides.

Home theater has always been about bringing the cinema experience home—to capture the movie-house magic in your own space without the impediments of traffic, parking, seat location, gum on the floor, and noisy neighbors. Yves Faroudja always said his goal in video engineering was to electronically bring the quality of projected film to the home. During my time at Faroudja, it was my pleasure to learn about and experience many iterations and applications of developing technologies in pursuit of that goal.

As video technology goes, there are two important developments in achieving visual realism: the arrival of high-resolution (1080p) digital projectors and high-quality sources (HDTV, Blu-ray, or HD DVD) delivered by a completely digital signal path. The ListenUp theater uses one of the latest 1080p three-chip e-cinema projectors from Runco, who, in their own way, have also pioneered the arrival of film-like experiences into our homes.

The icing on the cake is the revolutionary use of anamorphic lens technology to ensure that every pixel of native resolution a digital panel has to offer is available on the screen, no matter what the aspect ratio or source material. The impact of the video system becomes complete when these full-resolution images are projected on an expansive 170-inch-wide Stewart Firehawk four-way masking screen. This means there are no bars, no matter what, ever.

The screen incorporates Stewart's latest microperforated technology, which is designed to work well with the DLP projector and transmit audio from behind and through the projected image in the most realistic way possible. The four-way masking is automatic and controlled by the Crestron system.

I think of cables, bandwidth requirements, connectors, terminations, routing, switching, the integration and control to get all these diverse—and all too often fussy—components working together properly. For our clients, system control and integration become obsessive focal points. The words, "Can you please make it simple?" are uttered millions of times between system design and implementation. Clients are scared to death their theaters will not be easy to use, and, given the complexities involved, their fears are often well founded, if not fully realized.

Very few integrators have the programming horsepower and experience to pull off a control job as seamlessly as ListenUp has accomplished in their theater. The Crestron control system is integral to the experience in the ListenUp theater. Its design is logical and intuitive throughout routine operations. The last beep heard when the anamorphic lens and masking curtains slide into place instills you with a real sense of power and control. Think heavy equipment operator.

The ListenUp room is home theater on a massive scale. By way of comparison, I own a 1080p projector. I have a 100-inch-wide Stewart screen, I use Genelec monitors (smaller 10-inch versions of the ones in the ListenUp room), and I have two big subwoofers that make my windows rattle. On two occasions, they've even brought the cops. Yet, when comparing the experience in my room to the one in ListenUp's, the difference is profound and visceral.

This spring in Denver, Steve Weiner and I spent a good part of an afternoon and evening watching clips from our personal stashes, ignoring our cell phones and enjoying the pure adrenaline buzz that comes with the performance of their theater. Keith Yates' audio work in that room is unlike anything I've ever witnessed. Steve played the thunderstorm scene from Walk the Line. The lightning flashed, and the thunder rolled, and I had simultaneous overwhelming thoughts of being hit by lightning and of getting wet. When your physiology gets affected like that, it's definitely time to reach for the checkbook.

The ListenUp theater is certainly an accomplishment on many levels. I think the thing that probably most resonates with me is the commitment the folks at ListenUp have to the continued evolution and relevance of the project. Their unabashed pursuit of large-scale theater perfection makes a clear, inspirational statement about the nature and purpose of custom installation and why our clients should feel comfortable putting their trust in us.

- Log in or register to post comments