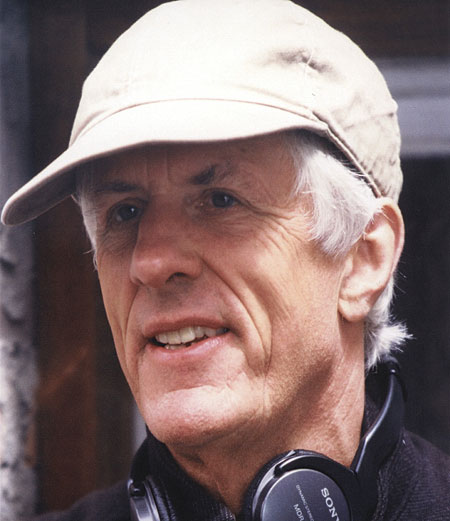

HT Talks To . . . Michael Apted

Before he embarked on a distinguished career in feature films (Coal Miner's Daughter, Gorillas in the Mist, The World Is Not Enough, and many more), director Michael Apted was part of a revolutionary British-television documentary project. It was called Seven Up, and it profiled a group of children in 1964. Apted took over from director Paul Almond starting with the first follow-up, 7 Plus Seven. He rounded up the same subjects at age 14 and has gone on to shepherd the series through to the present day. The films have become increasingly powerful for their ever-expanding scope and their ability to effectively condense entire lives of everyday citizens in a matter of minutes. 49 Up is the most recent installment, on DVD from First Run Features. All of the previous iterations are also available in an extraordinary boxed set.

Let's start with a bit of trivia: The title Seven Up comes from the name of the soda, correct?

No, it doesn't. I don't even know whether they had that soda at that time. It was more, "Give me a child until he is seven, and I will show you the man"—and then up and onward, as it were.

At what point did you realize that this would be a lifelong project?

I think it became clear when I'd done the second one, 7 Plus Seven, when we cut the stuff together, that here were the beginnings of a very powerful idea. Between 21 and 28, I'd moved to America, and there was some question whether the project would die. I remember going back to Manchester and sitting down with the guy who was running the company at that point, and he said, "We presume this is over now." And I said, "Not at all; it's at the top of my list." I made a commitment: Wherever I was living in the world, I would make sure that, every seven years, I would be back to do it.

In general, how do the subjects tend to view this project when you come back into their lives every seven years?

A few of them embrace it and are happy to see me and ready to go. But I would say the majority range from apprehensive to hostile to it.

How hard do you take it if someone says, "No, I don't want to do this anymore?"

I take it very badly. I do everything I can to avoid it. And I do everything I can to kind of foster goodwill during the seven-year gap and to make sure people are ready for it and prepared to take it seriously.

Do you send out Christmas cards?

Yeah. When I have an event in London, if I've got a film opening, I'll invite them along. I'm sort of mortified when people pull out.

From a logistical standpoint, how hard is it to manage all of the footage?

It's difficult, but it's helped vastly now by the fact that we cut on Avid [the industry-standard digital editing system], which we've had for the last two generations. You know, everything is sort of "press of a button." So, it does make it technically much easier than it was, but what's difficult is to marshal the stuff and not make it endless, you know? It does sort of cut itself in some ways, because some people have had an interesting seven years and some less so. There's no formula to it; they don't each have to have 15 minutes.

So, is it your intention to completely re-edit the movie each time?

Yes. I mean, there are the certain "golden oldies" that will always appear, but, yes, I think that's the key to it. When you look at the boxed set and look at the films, you can see how different they are. It's remarkable. I chuck out at least 85 to 90 percent of the previous film—not the archival stuff of the film, but of the previous generation of stuff.

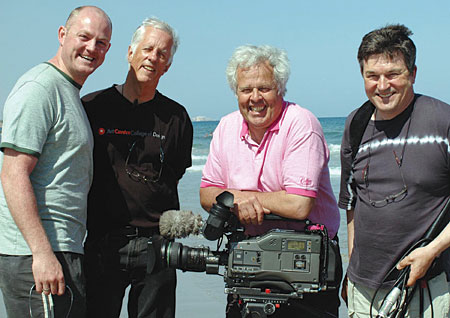

The 49 Up crew on location. Camera assistant Jason Trench, Apted, cameraman George Jesse Turner, and sound man Nick Steer.

But it's not necessarily longer each time.

No, I keep it the same length because I think you can only watch a certain amount of this stuff before you go mad.

49 was the first one you shot digitally, right?

Yes, I think it's helpful for me because I can do much longer interviews. You're not changing rolls every 10 minutes. I love film as opposed to digital. It has a texture that I love, but I think I get more out of it than I lose by moving from film to digital.

Would you ever shoot a feature film digitally?

I have a couple of projects that are very down and dirty, and, for that sort of stuff, when you absolutely don't want it to look glamorous and beautiful and you want it to have an immediacy and a roughness, I think digital can be very, very good.

Do you ever find yourself wishing that Paul Almond had shot his footage in color so that it would all match?

[laughs] No, I think it's a nice kind of clue to the passage of time. I don't say, "You're in 1985," you know, little things like that. I think it gives the film a sense of scale and the range of it that it started way back then.

When I watch the movies, I look past the differences in the school systems or the politics and just sort of zero in on the universal truths.

That's right. That's how the film has changed. It lost its political drumbeats fairly early on and became taken over—as it would have to be really—by the characters of the people. The politics of the film are still there as an undercurrent. But I think the film organically changed its point of view, and, in doing so, it became of broader interest and more accessible.

Back row: Steer, Turner, producer Claire Lewis, Apted, PA Jackie Turner. Front row: interview subjects Lynn, Susie, and Jackie.

I've heard that working within the James Bond franchise can be a strange, somewhat limiting experience.

Yes. I mean, they're very, very nice people, and I had a great time once I got the hang of it. But there were rules of the franchise, certain things you had to deliver that people would be expecting. So, the fingerprints you left on it were pretty slight. But, from my point of view, it was tremendous, interesting, and engaging to do that sort of film, to have to deal with the big budgets and to have to deal with that sort of scale. But, if you think you're going to go in and rewrite it all, then you're bound to have a miserable time.

And now you'll always be part of something that goes back and will continue and means so much to so many people.

Exactly. And people have expectations, which is rather thrilling and also frightening. You don't want to screw up and let them down.

How long do you see yourself staying with the Up series?

Oh, I think as long as I'm compos mentis. I mean, as long as a lot of them don't just drop out all of a sudden. I don't think it's going to get less interesting as we have to deal with age and mortality and all this sort of stuff. So, as long as I've got my marbles, I think I'll still keep it going.

With the technology a thousand years from now, people will have the Up movies as a window on this span of time.

Yeah, one would hope. I suppose my simple wish is that it does survive in some form or another in the years to come.

- Log in or register to post comments