I wish Pono all the luck in the world...I'm just not sure there's a big enough market willing to pay that much for music anymore.

High-Resolution Harvest Page 2

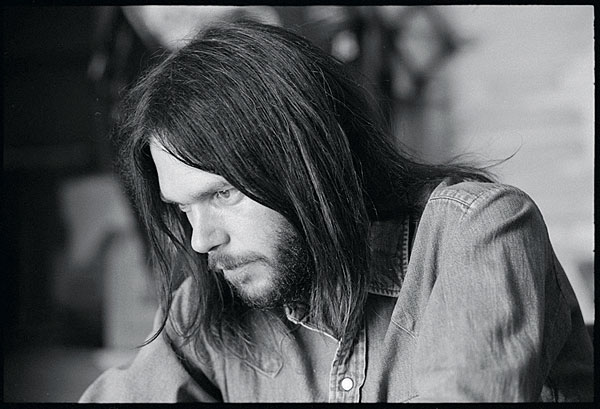

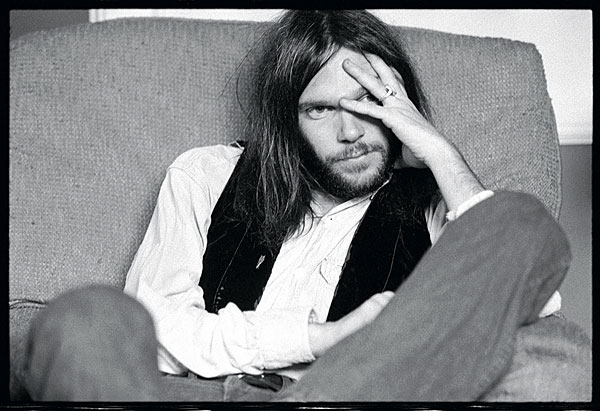

Hamm shares his own specific song examples: “You may not have realized there was a snare drum in Neil’s ‘Heart of Gold’ recording [played by drummer Kenny Buttrey], but you will now. You can listen to ‘Sympathy for the Devil’ and hear Mick Jagger laughing and coughing at the beginning of the track—something completely not possible to hear on MP3. There’s a Blood, Sweat & Tears song called ‘Spinning Wheel,’ and I’ve never heard the cowbell in it sound like it does on a PonoPlayer. And there are nuances on the vocals of Roberta Flack’s ‘Killing Me Softly with His Song’ that will bring you to tears. That level of realism is the actual difference people will be so moved by.”

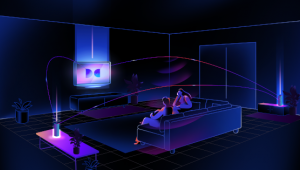

And what do people say when they listen to music on a PonoPlayer? “What most people report is there’s a separation, a staging, a spaciousness,” Hamm says. “They don’t know audiophile terms like soundstaging and depth, but they report the instruments are distinct from each other. The thing is, the level of compression that goes into MP3 essentially kills stereo separation. Just the notion that there is a distinct left and right, so it actually feels like there’s a left and a right to the staging, is all back again.”

Well, to paraphrase Young, there are only so many words between the lines I can take at face value, so I had to hear Pono for myself, and I joined Hamm for a Pono listening session in New York. See the “The Pono Session” for my impressions.

The Pono team has brought aboard and/or put on retainer producers/engineers like Bruce Botnick (The Doors, the original Star Trek film franchise), Niko Bolas (Neil Young, Warren Zevon), and Damien Page Lewis (Michael Jackson, Keane) to vet the music they receive, as they recognize what comes from record company vaults sometimes may not be what they want to release. As Hamm explains, “These are the people who know the providence of this music. They can tell the original masters from what got upsampled.”

Hamm stresses the files Pono uses will not be tampered with. “We don’t touch this music,” he says. “People ask, ‘Aren’t you going to remaster it?’ We’re not. We’re not going to touch it. Only an artist can sign off on any remix.”

I Am a Child, I’ll Last a While

So what do younger listeners think of Pono? Do they even care about sound quality? “I’ve heard Pono referred to by members of the MP3 generation as ‘vinyl you can take with you,’ ” says Young. “They think it is vinyl. To them, vinyl is like an adjective.” In one of the video testimonials posted on ponomusic.com, one teenager exclaims, “It’s like listening to vinyl in the palm of your hand!” while another marvels, “It sounds like you’re in the mixing board.”

Continues Young, “When kids hear Pono, they go, ‘Oh my God—I’ve got to have that. Where can I get it? Can I keep this? This is the way I want to live. I’m hearing things I never heard before in a song I’ve listened to 100 times. I feel like I’m in the room with the people making the music. How is this possible?’ And that’s good.”

“The myth was, kids don’t care about sound quality. I’m telling you, it’s just categorically not true,” insists Hamm. “As a businessman, I don’t know whether kids will pay for it, or if they’ll feel it will be a pain in the neck to download or subscribe to, or what they’ll do commercially. But the first job was to find out if they’d notice and/or care. If, given a choice, could young listeners discern a difference, and was one more pleasing than the other? I don’t think the answer is going to be a surprise anymore.”

I’ve Got the Real Thing, Baby

Pono’s stated goal is quite straightforward: Give listeners the option of high res as a choice. “We’re not making that decision for anybody. It’s up to the people,” confirms Young. “We’re just creating a situation where we’ve opened it up. That’s the beauty of it.”

Adds Hamm, “There’s nothing confusing about our mission, and that’s what Neil has said about it. All we really want to do is give people a choice, not an edict. There’s nothing wrong with you if you don’t want to do it. Neil’s point of view is the music will speak for itself. Artists believe MP3 is not a very interesting representation of who they are. They didn’t get a choice there; the world ran away from them on convenience. We’re trying to give people who have a value system related to their passion for music a choice. Who am I to judge what matters to them?”

Young feels the inherent quality of the music will be what propels Pono into the future. “Listeners are all basically going to hear what I did,” he says, referring to the core essence and intent of the music he’s been making for over six decades. “And I think what I did was the best that I could do. The music speaks for itself.” And from this point forward, it will all be speaking in high res. Or, to put it another way: My my, hey hey, sound quality is here to stay.

Read about our first listen impressions of the Pono hardware and software in The Pono Session.

- Log in or register to post comments

I'm all for the best resolution offering from any artist, but I do not believe that the cost of these offerings should be more than a physical copy of the music. When you eliminate the costs of the physical medium, manufacturing, warehousing, shipping, stocking, etc., the cost of a physical copy should be more than that of a "ether" version stored on a server. Until the price equalizes with that of a physical copy, I will stick with CDs.

I absolutely agree with huempfer. I love great sound but, like the average lower-income audiophile who can't afford custom-built speakers that cost $239,000 a pair (really, S&V? Really?), I have to be quite frugal when buying equipment but the great thin about modern electronics is how relatively inexpensive it can be to build a decent home theater system for both music and movies. But a few months ago I purchased the SACD of "Dark Side of the Moon" oa Amazon for about $11.00, and I'll be damned if I'm going to pay another $25-$30 for another copy that, like huempfner says, is basically thin-air, with barely any overhead costs. But it's just not hi-res. Does anyone honestly believe an iTunes or Amazon download is worth $.99 -$1.29 for a song ripped to a compressed format?